Many relevant diagnostic signs are not performed deliberately by the examiner or by the patient at the examiner’s direction. They are observed as the patient reacts to their condition. Fortin’s finger sign, Minor’s sign, and Vanzetti’s sign are three examples of this principle.

Chiropractic Scope of Practice, Part I

This commentary is reprinted from the September 1993 issue of the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, Vol. 16, Number 7. Because of its length, the article will be presented in three parts.

As chiropractic approaches its centenary, amazingly, the question of what is the appropriate chiropractic scope of practice remains unanswered. The question is an important one. How it is answered will determine which patients have access to chiropractic care, the nature of that access (direct or referral) and how that care is paid for. This question continues to generate considerable debate and disagreement throughout the profession. Chiropractors describe themselves as anything from a primary care provider to back specialist to subluxation doctor. Up to this point the profession has survived and even flourished despite the lack of consensus on this issue. However, I believe the time rapidly approaches when we can no longer afford to present such a confused and muddled image of the profession.

It is everywhere said that there is a crisis in health care. Within a year or two the cost of health care in the U.S. will exceed $1 trillion and consume 15% of the GNP. On a per capita basis, this is more than twice as much as the next most profligate country (Canada). In spite of these enormous expenditures, the U.S. ranks well down the list on many indices of health. A variety of solutions to the problem have been offered and although there is at present no consensus on a solution, there is general agreement that profound changes are necessary. One change on which there is agreement is that in the future all health care providers will be held to a higher level of accountability than they have been in the past. The various health care professionals will be required to demonstrate that what they do really makes a difference and that their respective services are appropriate for a given patient population or condition. This will probably translate into there being more rather than less participation of, and regulation by, the federal government in the delivery of health care.

Looming over the entire debate is the possibility of a national health insurance program. This discussion proceeds under the assumption that it is necessary for chiropractic to be a part of any national health care reform, that we be an integrated element of the total health care delivery system. There are members of the profession who see matters quite differently, who feel the role of chiropractic is to be apart from the rest of the health care system, to be a comprehensive alternative to that system, rather than being adjunct to it. To those so inclined, I doubt the balance of this discussion will be very persuasive.

A recent report commissioned by FCER addressed the question of what the chiropractic profession must do to gain access to federal funding for education and research.1 Although addressing only this narrow question of funding, the report might also be read as addressing the question of what the profession must do to ensure its inclusion and participation in any national health care reform. The report concluded that one of the primary impediments to achieving the desired acceptance by government health policy makers is the profession's lack of a coherent and credible scope of practice. In particular, the report focuses on the profession's use of the term "primary care" to describe its scope of practice.

Interestingly, given the major differences that exist on many issues, there is remarkable agreement among the educational and political institutions within the profession on the use of this term. The term "primary care" (PC hereafter) appears in the catalogs of chiropractic colleges representing every point along the professional spectrum. It is found in the mission statements of National College, Northwestern College, Los Angeles College, and it is also found in the mission statements of Palmer College, Life College and Sherman College. For the most part this term, PC, goes undefined in these documents. Similarly, the principal political organizations in the profession, the ACA and ICA, are in agreement on this issue. They also use the term PC, undefined, to describe chiropractic scope of practice.

That these widely disparate groups with vastly dissimilar aims and objectives, should describe chiropractors as primary care physicians suggests not that this concept has broad appeal, but that the concept has been largely unexamined. What, exactly, does it mean to say that chiropractors are primary care physicians? Does this mean that chiropractors are like medical family practitioners except that they don't prescribe medication and they do adjust spines? Or does it mean something else? To my knowledge, that question has not been answered by those advocating the primary care position. The phrase "chiropractors are primary care physicians" has been spoken almost as a mantra without exploring the meaning of it. I believe most of the confusion and at least some of the disagreement over scope of practice arises from not having adequately explored many of the terms and concepts under discussion. These terms include "primary care vs. portal of entry," "limited provider vs. nonlimited providers," and "diagnostician." This commentary will examine the meaning of primary care and other concepts as they apply to chiropractic and will offer an alternate scope of practice model.

Primary Care

What is primary care physician? The definition of PC that is recognized by the federal government is one that was developed by the National Academy of Sciences.2 This standard identifies a number of conditions that must be met to qualify as a PC physician including accessibility of services, coordination of services with other providers, continuity of services, and several others. We chiropractors would have some difficulty meeting several of these conditions, such as accessibility of services (available 24 hours a day, seven days a week), but could presumably meet them if we really wanted to. But there is one condition, comprehensiveness of services, that cannot be met. This is defined as the ability to manage without referral 90% of the problems arising in the served population. Thus, a PC physician may limit his practice to a particular population -- like a gynecologist, pediatrician or an internist -- but within that population the PC is expected to manage without referral, 90% of those patients' problems. Explicitly mentioned is the management of infectious diseases, providing immunizations and managing minor trauma (lacerations). The essence of a primary care physician is being a generalist, not a specialist.

One important distinction should be made at this point. That is the difference between a PC physician and a portal of entry (POE) physician. A POE provider is any physician to whom a patient had direct access, not referral access. In other words, a patient can pick up a phone book and call and make an appointment with a POE physician. Dentists and optometrists are types of POE physicians but they are not PC physicians mainly because they do not provide comprehensive care. Hence, all PC physicians are POEs, but not all POEs are PCs.

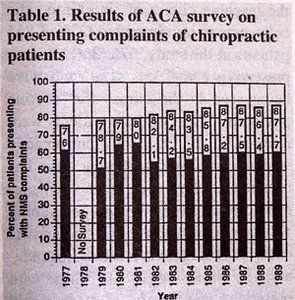

How do chiropractors measure up as generalists? There are a number of studies that have examined the conditions for which patients see chiropractors. From 1977-1989 (there was no survey in 1978), the ACA conducted an annual survey that asked its members what percentage of their practices involved the treatment of neuromusculoskeletal conditions.3 Table 1 shows the results of that survey. That percentage has increased steadily since 1977 and seems to have leveled off at about 87%.

Percent of patients presenting with NMS complaints

A survey by Phillips, rather than asking the doctors what they thought their patients' presenting complaints were, asked patients to fill out a form on which they recorded their primary complaint.4 Results are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Patient response form Phillips4

Pain (head and neck, thoracic, low back-pelvis, peripheral) 90.4%

Restricted motion (neck, thoracic, lumbar pelvic, extremities) 2.9%

Neurological (paresthesia, hyperactivity, paralysis, numbness) 1.3%

Organic (cardiovascular, genitourinary, gastrointestinal, 2.1% endocrine, respiratory)

Prevention or maintenance 1.4%

Other 2.3%

The first three categories would fall under the heading of neuromusculoskeletal complaint. Collectively they total 94.6% of the patient population.

Consider one final datum on this subject. The author reviewed the last four years (1988-1991), inclusive of the JMPT, and identified all original articles, case studies and reviews of the literature where a particular clinical entity was the primary focus of the paper. One hundred twenty-nine such papers were identified. Of these, 108 (84%) dealt with neuromusculoskeletal problems (back, neck, extremity problems), while 21 (16%) dealt with all other conditions (dysmenorrhea, colic, asthma). I'm sure this comes as no surprise to readers of this journal. This merely indicates that the clinical interests and expertise of the academic and scientific community within chiropractic parallel that of the practicing DC.

One could keep piling on redundant statistics from public opinion surveys and insurance company information, all of which show that what chiropractors do and how we are perceived is consistent with that of a neuromusculoskeletal specialist. I am unaware of any study or survey that suggests that, at least the way chiropractic is practiced, it is anything other than a neuromusculoskeletal specialty. At this point it seems that the best case that can be made for the DC and PC is that, while chiropractors currently do not practice as PC provider, they aspire to.

In one sense, the question of whether chiropractors are PCs is a trivial one. The answer is no, just as the answer to the question, "Are chiropractors astronauts?" is no. By definition, primary care providers and astronauts do certain things (treat pneumococcal pneumonia and orbit the Earth, respectively) that chiropractors do not. Of course it can be argued that the definition of primary care should be expanded to include chiropractic, but really, what's the point? One would first have to convince the health care establishment that things like antibiotics, immunizations and insulin are not really important parts of primary care. This is not likely, in the extreme.

Let's assume for the moment that a convincing case can be made (though I don't believe it can) that there is another sort of primary care that does not rely on these medical therapeutic modalities. This DC/PC provider would act as the diagnostician and gatekeeper much as a family practitioner or internist might and treat the patients or refer as indicated. (I'll not argue the point of whether or not DCs are diagnosticians; we are).

For chiropractors to describe themselves as PC diagnosticians (if that is the case being made) is to invite comparison to other PC diagnosticians, i.e., medical primary care physicians. The FCER study cited earlier compared the curricula of several chiropractic and medical schools.5 The University of Minnesota Medical School and Northwestern College of Chiropractic were used as examples of their respective professions. Both chiropractors and MDs receive their degrees after four years of training. These four years total about 4500 hours of training in both curricula. The first two years of instruction in chiropractic and medical schools are roughly equivalent, being spent mostly on the basic sciences and on introductory clinical courses. Chiropractors can actually boast of having more instruction in several of the basic sciences (anatomy, physiology, etc.) than their medical counterparts. Additionally, in the first two years the chiropractic curriculum includes classes on various adjustive techniques and classes relating to specific orthopedic, spinal or neurological problems, i.e., neuromusculoskeletal problems. The medical curricula contains none of these classes but does offer significantly more training in pharmacology. These differences are predictable and appropriate.

In most medical schools, classroom instruction has effectively ended after those first two years. The last two years are usually spent in a series of clinical externships in fields such as internal medicine, obstetrics, gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, and other primary care specialties.

The last two years of chiropractic education offer a continuation of the technique classes, adjustive and otherwise, and a continuation of the neuromusculoskeletal related classes. The balance of the didactic instruction is in the classroom equivalent of those primary care specialties mentioned above. The key word here is classroom. These are essentially lecture classes that may or may not have a lab component. The lab component typically consists of demonstrating and practicing exam procedures, videos or patients or patient simulations. These classes do not usually offer any contact with actual patients. How could one argue that a 30-hour lecture class (no lab) in pediatrics or a 67.5-hour class (60 lectures, 7.5 lab) in ob/gyn, or a 30-hour lecture class (no lab) in infectious disease is in any way the equivalent of spending six weeks in a patient care facility in each of those areas?

A similar comparison of chiropractic medical, and osteopathic colleges appearing in the Journal of Chiropractic Education showed a similar pattern.6 That study compared the total number of hours spent in classroom and in clinical settings at each school. The chiropractic school averaged 800 hours (17.6%) out of 4540 total hours in an outpatient clinic, whereas the medical school figures were 2825 clinic hours (62.8%) of 4495 total hours. A brief survey of the chiropractic colleges' catalogs suggests that a figure of 800-900 hours of clinic-based training is typical.

It is also worth examining the nature of those 800-900 hours of clinical experience. A study by Nyiendo and Olsen7 on presenting complaints of patients at the teaching clinics of six chiropractic colleges is most informative. Of the 1865 patients in the study, 676 (36%) had no presenting complaints at all and were being seen in the clinics for "routine physicals." Most of these patients were referred to the clinics by chiropractic students and interns. Anyone who has ever been to chiropractic school will recognize this as chiropractic students doing what they have to do to get the requisite number of patients visits needed to graduate. The remaining patients (those with presenting complaints) were classified as having problems with low back, upper/mid-back, neck, head, extremity or other (other referring presumable to non-neuromusculoskeletal or visceral-type complaints). Patients in the "other" category numbered about 6% of the symptomatic patients or about 4% of the total patient population. These figures closely parallel those of the Phillips study cited earlier.4 If we assume that a chiropractic intern sees 50 new patients (a generous figure) in the course of his or her clinical education, these figures translate into each student seeing two patients with something other than neuromusculoskeletal complaints during their internship. Unless the clinical education of the chiropractic colleges not included in this study is markedly different from those in the study, and there is no reason to believe it is, then I do not see how it can be argued that chiropractic colleges provide a clinical experience comprehensive enough to function in the same clinical arena as family practitioners.

It must also be pointed out that nearly all chiropractors go directly into practice following their four years of training, whereas nearly all MDs including family practitioners, internists, etc., spend an additional 3-4 years in residency training.

One could argue it is unfair to compare chiropractic training and medical training in this manner; chiropractors and MDs serve different roles in the health care system. Precisely. The MD/PC training is directed at creating a generalist. The content and duration of that training is a reflection of that. Quite sensibly, chiropractic training focuses on those conditions and problems that most commonly present in the DCs office, as well as providing enough generalist background to function competently. You might say that chiropractors major in neuromusculoskeletal and minor in PC. But again, as long as chiropractors describe themselves as PCs we will invite these comparisons, and they are not comparisons that are likely to reflect favorably on chiropractic. None of this is an argument that chiropractors should limit their clinical training to a narrow neuromusculoskeletal experience. On the contrary, I believe that we must, as some schools have already done, expand our clinical training to include hospitals, emergency rooms, and other medical care facilities. But this should be done not to become qualified as PCs, but to become better DCs.

Another concept that requires examination is that of limited vs. non-limited practitioner. Many chiropractors strenuously object to being described as limited practitioners. This seems a silly discussion. No one profession or specialty, certainly no individual doctor, can provide "unlimited" health care services to the public. The question is not, "Are chiropractors limited practitioners?" Of course we are limited, as are all health care providers. The real question is, "What are chiropractors' (or any other practitioners') limitations?" A brief list of those limitations would include the following:

1. Chiropractors do not prescribe antibiotics.

2. Chiropractors do not prescribe anti-inflammatory medications.

3. Chiropractors do not perform surgery.

4. Chiropractors have limited expertise and experience (or not at all) in certain diagnostic procedures (pelvic, exam, proctoscopic exams, endoscopic exams, etc.).

These are not trivial limitations. All the above listed procedures are useful and necessary elements of any health care system. It is nonsense to suppose that not providing these services does not impose significant limitations on the practice of chiropractic. At the same time it is not necessary to apologize for those limitations. These are, for the most part, limitations by choice. Indeed, in may respects, it is precisely these limitations, our self-imposed conservative range of therapeutic and diagnostic modalities, that is one of the major strengths of chiropractic. By not providing those services, chiropractic is necessarily a more conservative discipline that, when it is practiced appropriately, usually translates into a cheaper and safer intervention.

In this context (limitations), consider the various medical primary care physicians. Each of these has its own set of strengths and weaknesses (limitations). A gynecologist is more skilled at pelvic exams than is a pediatrician, who is more proficient at evaluating a febrile infant than is an internist, who has more experience with angina than does a family practitioner, and so on. We can add to the list of limitations for each of those, the following:

Perfunctory training and limited diagnostic and therapeutic experience in the management of common neuromusculoskeletal disorders.

This limitation applies to nearly every medical physician except those who are not commonly portal of entry physicians, i.e., orthopedic and neurosurgeons and neurologists. Thus, we seem to have a niche in the health care marketplace that needs filling: a portal of entry physician for neuromusculoskeletal conditions who treats most of those conditions and refers to secondary and tertiary providers (surgeons and neurologists) when necessary. This is exactly what chiropractors actually do. The problem is that the profession has been unwilling to overtly embrace this role. To those who insist that chiropractors are primary care physicians, I must ask the question: What do we offer as evidence that this is true?

Craig Nelson, DC

Northwestern College of Chiropractic

2501 West 84th St.

Bloomington, MN 55431-1599

References

- FCER. An evaluation of federal funding policies and programs and their relationship to the chiropractic profession. 1991.

- FCER. An evaluation of federal funding policies and programs and their relationship to the chiropractic profession. 1991:23-4.

- ACA. ACA department of statistics 1989 survey. JACA 1990;Feb:80-1.

- Phillips R. Survey of chiropractic in Dade County, Florida. JMPT 1982;5:83-9.

- FCER. An evaluation of federal funding policies and programs and their relationship to the chiropractic profession. 1991:67-92. FCER.

- Ratliff C, Rogers S. Comparison of core curriculum courses common to chiropractic, medical, and osteopathic schools in Missouri. J Chiro Educ 1990;Dec:76-80.

- Nyiendo J, Olsen E. A comparison of patients and patient complaints at six chiropractic teaching clinics. JMPT 1989;2:79-85.