Spearheaded by burgeoning scientific and clinical research literature, psychedelics have reached a level of media coverage and popular interest that has not been seen for over half a century. By “psychedelics,” we are referring to the unique class of substances that includes psilocybin (the active compound found in so-called “magic mushrooms”), LSD, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), ayahuasca, 5-MeO-DMT, and mescaline – each of which occurs in the natural world (except for LSD, which is a semi-synthetic compound).

Show Me Chiropractic (Part 1 of 2)

Several years ago, I was rather surprised to hear from an officer in one of Missouri's professional societies that a history of chiropractic in the "Show Me State" would not be possible, because so little information was available. With two surviving chiropractic schools in the state, each with a tradition of historical preservation, that gentleman's perspective didn't ring true. After a dozen years of rummaging through the Cleveland College historical collection, and three years with the Logan Archives, I can say with confidence the following: 1. Missouri has one of the richest, most colorful histories in the profession; 2. The state's two surviving schools have preserved an enormous amount of historical materials; and 3. There is much to be discovered and documented from the available records. I haven't explored the Missouri-relevant holdings in the Special Collections section of the David D. Palmer Health Sciences Library in Davenport, but given the well-known hoarding tendency of Dr. B.J. Palmer, a rich yield is anticipated.

Because Missouri is the Show Me State, perhaps a few pictures will do more than words to stimulate historical interest. Let me preface this by noting that the Cleveland historical collection predates the Civil War, and thus provides not only a window on chiropractic history, but on the nation's saga as well. The collection at Logan is so extensive that its contents are not fully known; cartons and cartons of unsorted materials await classification and preservation. In short, there is ample material at these two colleges to keep several archivists and historians busy for a long time to come!

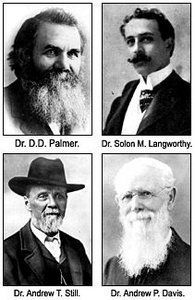

D.D. Palmer's brush with death in 1897, during a railway accident in Fulton, Mo., suggests that chiropractic had come to the Show Me State even before the turn of the century. Solon M. Langworthy studied at the American College of Manual Therapeutics in Kansas City in 1902, apparently just after completing his studies with D.D. Palmer, and before establishing the first serious competitor to the Palmer School: the American School of Chiropractic & Nature Cure in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.9 The presence of a school of manual therapeutics in Missouri was nothing novel, of course, since Andrew T. Still had been operating his American School of Osteopathy in Kirksville for a decade when Langworthy came to Kansas City. Another early Palmer graduate, Andrew P. Davis, MD, DO, DC, made several visits to St. Louis around 1908.8 This "itinerant schoolman" presumably left an impression of chiropractic as he had in so many other locales.3 In 1913, the recently formed St. Louis Chiropractic College, headed by L. William Ray, AM, MD, DC, effected a temporary merger with Alva Gregory, MD, DC, and Oklahoma City-based Palmer-Gregory College of Chiropractic.1

| Table 1: Chiropractic schools in Missouri2,4 | |

| Booker T. Washington Chiropractic College, Kansas City, 1946-1951 | Research Foundation College of Chiropractic, 1935-1937; (formerly Logan Basic College of Chiropractic, 1937-1964) |

| Chiropractic Institute and College, St. James, 1904-[19--] | Mid-West School of Chiropractic |

| Chiropractic Institute of Kansas City, Kansas City, [1914] | Missouri Chiropractic College, St. Louis, 1920-1964 |

| Chiropractic University, Kansas City [1913-1927] | Missouri Chiropractic Institute, St. Louis |

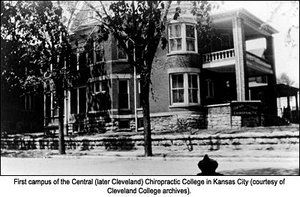

| Cleveland Chiropractic College, Kansas City, 1922-present (formerly Central Chiropractic College) | Mo-Kan College of Chiropractic, Kansas City, 1907?-1924 |

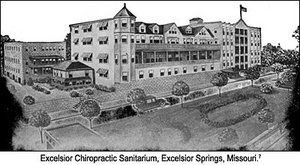

| Excelsior Chiropractic Sanitarium, Excelsior Springs [1934-1938] | St. Louis Chiropractic College, St. Louis, 1909-[1922] |

| Hughes College of Chiropractic, St. Joseph | Spino-Neural Chiropractic College [1925] |

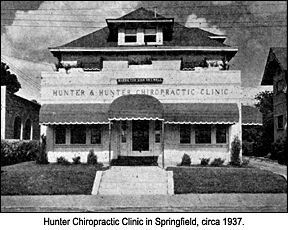

| Hunter School of Chiropractic, Springfield, [1925] | Springfield Chiropractic College, Springfield [-1922] |

| Logan College of Chiropractic, St. Louis, 1935-present (formerly International Chiropractic) | Western Chiropractic College, Kansas City [1927-1943] |

Carl and his bride, the former Rose Ruth Ashworth, had relocated there from rural Webster City, Iowa, with their young son, Carl Jr., in search of a larger population to support their clinical practice. In December 1922, they and fellow Palmer alumnus Perl B. Griffin, DC, Carl Sr.'s brother-in-law, chartered the nonprofit Central Chiropractic College (later renamed Cleveland Chiropractic College at students' request), and offered a curriculum that paralleled their alma mater's offerings, but with perhaps a somewhat stronger commitment to diagnosis and anatomic instruction by dissection.

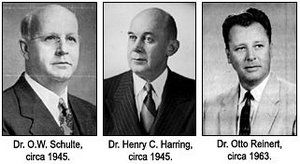

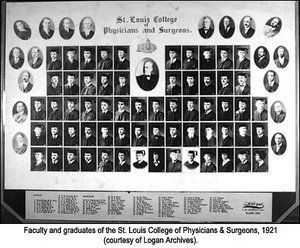

The Missouri Chiropractic College (MCC) was founded in St. Louis in 1920 by Robert E. Colyer, DC; Oscar W. Schulte, DC; and Henry C. Harring, DC. The first classes at this proprietary school were held in the Olivia Building at Grand Avenue and Windsor Place in St. Louis.5 Dr. Colyer served as MCC's first president until 1923, when he sold his interest in the school. He would later teach (1937) on the faculty of the International Chiropractic Research Foundation's (ICRF's) College of Chiropractic, better known today as Logan College of Chiropractic. Dr. Harring succeeded Dr. Colyer as president of MCC in 1923. By this time, Dr. Harring, a graduate of the St. Louis College of Chiropractic, had earned a second doctorate, from the St. Louis College of Physicians & Surgeons. He would continue as principal stockholder and president of MCC until 1962, when he passed the reins of the institution on to 1936 MCC alumnus Otto C. Reinert, DC.

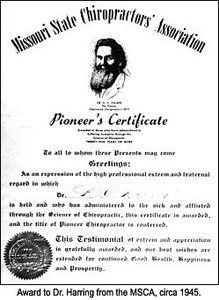

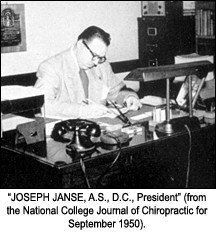

Although he was initially a straight chiropractor and remained firmly committed to the value of the adjustive art, Dr. Harring and his school would later become much more liberal in their orientation to chiropractic. Harring came to believe that students should receive training in broad-scope practice, and for this, he became something of an outcast in the eyes of the Palmer-Cleveland faction of the profession. Nonetheless, the mild-mannered Missourian was beloved in his home state, and earned honors from the MSCA. He was an activist in the educational reform efforts of the National Chiropractic Association in the 1930s-1950s, and a good friend of Joseph Janse, DC, ND, president of the National College of Chiropractic. When William N. Coggins, DC, president of Logan Basic College of Chiropractic (LBCC), resisted the notion of merging the MCC with his school, President Janse raised the possibility of a National-Missouri branch campus in St. Louis.5 This was enough to motivate Dr. Coggins, and the LBCC took over the MCC in 1964. Dr. Reinert became a faculty member and instructor in diversified technique at the now-renamed Logan College of Chiropractic.

Missouri chiropractors endured a good deal of persecution from political medicine in the early years. Carl Cleveland Jr., DC, recalled his father's efforts to celebrate the imprisonment of DCs who went to jail for principle by hiring bands to serenade imprisoned doctors outside of jailhouses. Missouri did not pass a chiropractic statute until 1927, and then only at the request of a funeral parlor owner, to whom the speaker of the state assembly owed an undisclosed favor.6 Jones Parker, LLB, MD, former member of the AMA board of trustees, delivered on his promise to the undertaker and subsequently became a repeated guest speaker at various state and national chiropractic conventions.

The introduction of basic science legislation, beginning in Connecticut and Wisconsin in 1925, threatened the viability of the profession in those states where chiropractic statutes had been passed. Basic science laws required would-be licensees (DCs, DOs, MDs, NDs) to pass tests in subjects such as anatomy, bacteriology, pathology, physiology, and public health prior to sitting for examination by their respective licensing boards. Basic science laws were often constructed and administered by faculty members at state university-based medical schools, and frequently failed to observe the anonymity of the graduate's respective profession. Chiropractors cried foul! The ranks of the profession were severely restricted in several states, such as Nebraska, where no new chiropractic licenses were issued for over 20 years, because no DC could make it over the basic science barrier.

References

- Consolidation. The American Drugless Healer 1913 (Aug);3(4):75-6.

- Ferguson (Callender), Alana; Wiese, Glenda. How many chiropractic schools? An analysis of institutions that offered the DC degree. Chiropractic History 1988 (July);8(1):26-36.

- Gibbons, Russell W. Joy Loban and Andrew P. Davis: itinerant healers and "schoolmen," 1910-1923. Chiropractic History 1991 (June);11(1):22-8.

- Keating JC, Cleveland CS. Cleveland Chiropractic: the early years, 1917-1933. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics 1996 (June);19(5):324-43.

- Reinert, Otto C. Merging with honor: a history of the Missouri Chiropractic College, 1920-64. Chiropractic History 1992 (Dec);12(2):38-42.

- Wardwell, Walter I. Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession. St. Louis: Mosby, 1992.

- What Chiropractic is Doing. Indianapolis: Burton Shields Co., 1938.

- Zarbuck, Merwyn V. Chiropractic parallax. Part 2. IPSCA Journal of Chiropractic 1988b (Apr);9(2):4-5, 14-16.

- Zarbuck, Merwyn V. Chiropractic parallax. Part 3. IPSCA Journal of Chiropractic 1988c (Jul);9(3):4-6, 17-19.

Joseph Keating Jr., PhD

Phoenix, Arizonajckeating@aol.com

[Editor's note: Part 2 of this article will appear in the March 12 issue.]